This posting is based on conversations and correspondence between Kathleen Walkup and Jeff Groves that have been edited for form, clarity, and concision. Kathy is Lovelace Family Professor Emerita at Mills College, now Northeastern University Oakland. While at Mills, Kathy inaugurated the first separate graduate degree in book art in the U.S. and later co-established the first MFA in Book Art & Creative Writing in the country. Jeff is the Louisa and Robert Miller Professor of Humanities at Harvey Mudd College, the founder of The First-Floor Press at the Claremont Colleges Library, and the inaugural faculty director of the Harvey Mudd College Makerspace.

Jeff: In our previous exchange, we suggested that studio art typically begins with concept and then moves towards technology, whereas makerspace practice often starts with technology and builds towards a project. So both the studio and makerspace environments are creative, but creativity is developed in different directions. Exceptions abound, of course! But in both environments, there are certain necessary, routine practices that artists and makers need to take seriously. Think about type distribution, for instance. In either environment, undistributed type is a tool that can’t be easily utilized without a significant investment of time by a new user. In the studio, I find it’s easy to insist on distribution–near the end of the semester I tell my students that I will check every galley in the rack, and I will not award a final grade to students who have not distributed their type. In the makerspace, though, there are no grades with which to discipline practice, and not necessarily any strong supervision of students using the letterpress station once those students have gone through a training workshop. Each time I walk by the press in the makerspace, I notice a bit more undistributed type on galleys, and so I’m working on how we can more successfully build distribution into the letterpress training and make the expectation of distribution a value in the user community.

Kathy: There is no question that, in the letterpress studio, handset metal type is the most vulnerable material. At Mills we not only withheld a final grade but put a student’s record on hold if their type was not dealt with; luckily, this rarely came up, although more than once I received a call from housekeeping to say that they had found some weird-looking letters in someone’s abandoned dorm room and wondered if they had anything to do with us. The way we were more or less able to keep the type in check was to constantly look through the galleys to make sure they were identified by type and student and then keep track of when that type was distributed. The studio manager always expected to have the studio lively with students on the very last day each semester when they could get in to deal with their type.

I once was invited to work in an academic studio where the community was allowed in one Sunday a month to print. While this was a noble gesture, it was literally impossible to work in that studio after several years of this: untied metal type spilled over on galleys, I couldn’t find two slugs that were the same length, and the collection of rare wood type was stacked in unruly piles on top of every type cabinet.

It may be that students in makerspace environments have to earn the right to use the type, which would otherwise be off limits. This might seem harsh, but we both know that a letterpress studio can become unusable in as little as six months if the type isn’t kept under strict control. Of course in studio classes, students support each other in their work. And while they rarely rat on someone whose individual studio practice is less than stellar, they do find ways to let someone know when a student is making work difficult for the others. I’m not sure how that concern for a workable collective environment translates when it comes to workshop or makerspace classes. What have you found?

Jeff: I think the answer will be found in community building. The HMC makerspace is largely student run. We have a staff manager, but beyond that we depend on more than forty student “stewards” to make the place hum. The academic literature about makerspaces suggests that having a student-run shop, instead of depending primarily on staff members, is a potent way to create a collaborative maker community, and part of creating that community is building norms or expectations for behavior. We do that through our student-developed policies and training programs. Within our steward workforce, we also have a group of six head stewards who work closely with the manager and me to direct the efforts of the other stewards. Training the stewards to compose and print just got underway this year, and I’m hopeful that as we begin to build some letterpress experience among the stewards, and as they in turn share that with other students through our training program, all our users will see more fully than they do now the need for proper distribution. I have great faith in our stewards. We can touch base again in a year to see how the community building is going. Beyond distribution, what other press-room practicalities do you see that might differ between studio and makerspace?

Kathy: Yes to community building! It sounds like you have found a great way to do this in the makerspace environment. In the studio environment, community is built by the instructor, of course, but also by teaching assistants. Before Mills had a grad program in book art, I developed a system for volunteer teaching assistants. These were usually students who had graduated from Mills but were sticking around the Oakland area, although in some cases I brought in students from other programs in which I taught, like Community College of San Francisco. The assistants got press and bindery access in exchange for a set number of office hours per week in which they were available to students who were currently in the classes. This was so successful that we kept up the volunteer TA program even after we had actual graduate assistants.

Speaking of graduate assistants: I had a great conversation with Rebecca Josephson, a recent graduate of the Mills MFA in Book Art who largely took over my classes when I retired. Becca has been teaching the workshop classes initiated by Northeastern University when that institution took over Mills. When she was asked to set up these courses, she initially had the same concerns about studio practicalities that you have had. What she did was, first, say no to teach one-off classes in which students would spend only one or two sessions in the studio. Instead she proposed four-session workshops in which students were given the time to develop a small project while they also learned basic studio practice in setting and distributing type, handling ink, elementary lockup, safe studio practice and, not least, press cleanup. While she was not happy to lose some semester-long classes, she did see that students were able to be excited about their projects while also learning to treat the studio with respect. What was missing, and what she particularly mourned, was the ability to have students in an open studio environment outside of class, since, in the absence of TAs, there was no one to supervise the time. And unless students can be trained to do those supervisory jobs over longer periods of time (by someone that the college is willing to pay as an instructor/supervisor) that option will most likely remain off the table. Becca has done an impressive job of making workshop classes work, and I have suggested that she might want to write a future blog post about her process.

Jeff: I appreciate Becca’s solution and that her new structure has allowed for student excitement. Perhaps the makerspace or workshop can serve as a gateway to more prolonged and rigorous studio practice? I think I’m seeing some developments in that direction with my fall enrollment. A fair number of makerspace stewards who I trained to use our letterpress station have enrolled in my for-credit course. I’m hopeful that they’ll then return to the makerspace with much more expertise and a greater sense of how to keep the whole operation running. We’ll see!

In the meantime, Kathy, we should probably stop here, but only after inserting some photos of our respective spaces! Good as always to talk to you. I hope our conversation spurs some further discussion, and I also hope to see a posting from Becca in the not-too-distant future.

The First-Floor Press at the Claremont Colleges Library.

The letterpress station in the Harvey Mudd College Makerspace.

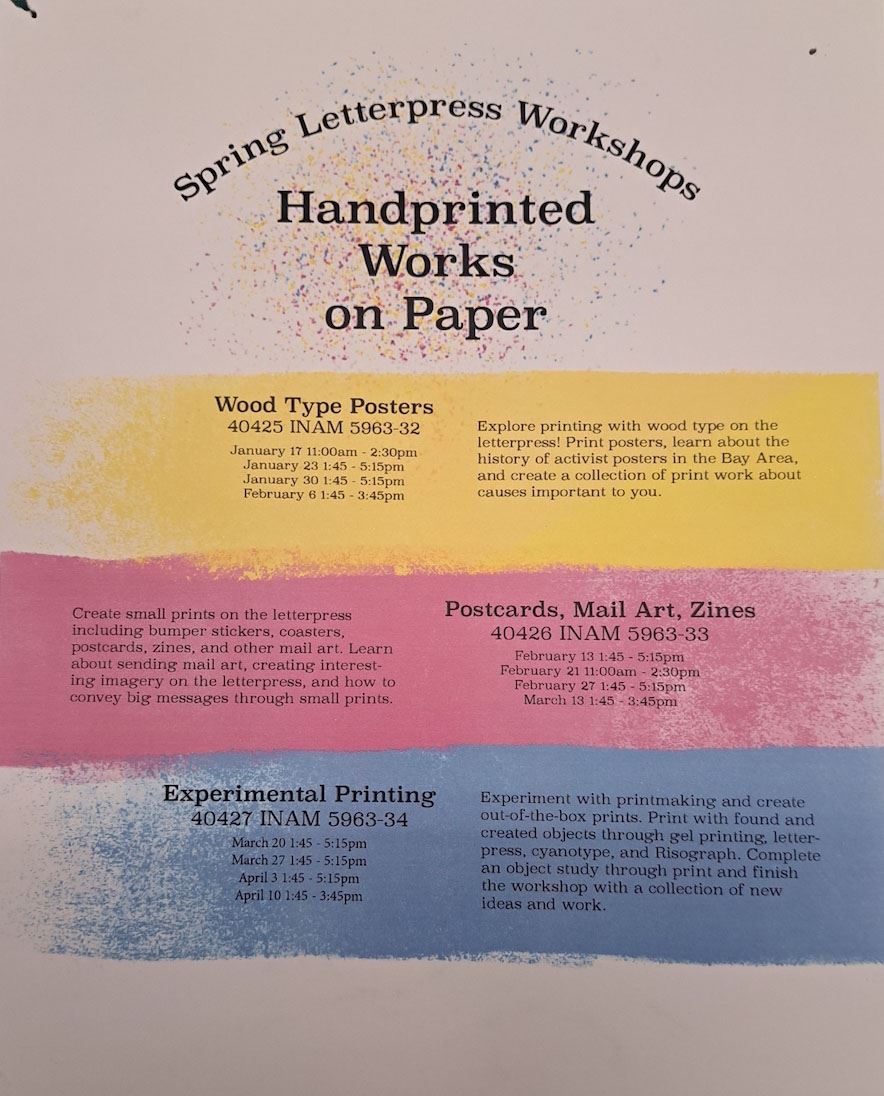

Poster for spring 2023 workshops in the Mills letterpress studio taught by Rebecca Josephson, who designed the poster.