Why do so many people, when first exposed to the book arts, find themselves enthralled?

I think a large part of it is in the physicality of using their hands in the processes they’ve just been exposed to.

Many people now have never played in a sandbox or have forgotten the simple joys of playing in the dirt. But we all started our lives finding out about the world by using our hands to touch it, feel it, taste it, and having our fingers cut and burned.

Here in the twenty-first century, as you know, our lives are increasingly filtered through disembodied electronic portals – screens that flatten our experience, distancing us from direct engagement with the physical world, antithetical to the deeper connections and texture we need to feel fully human. The book arts serve as a restorative, of physical action combining with intellectual activity and content. People new to book arts can be startled with a recognition of what they’ve been missing or have forgotten they had the capacity to do.

Over the centuries writing has been an expression of societies and broader cultures. For example, Northern European mediaeval societies had variants of spiky architecture, spiky writing and spiky hierarchical thinking. It was a little less severe In Southern Europe.

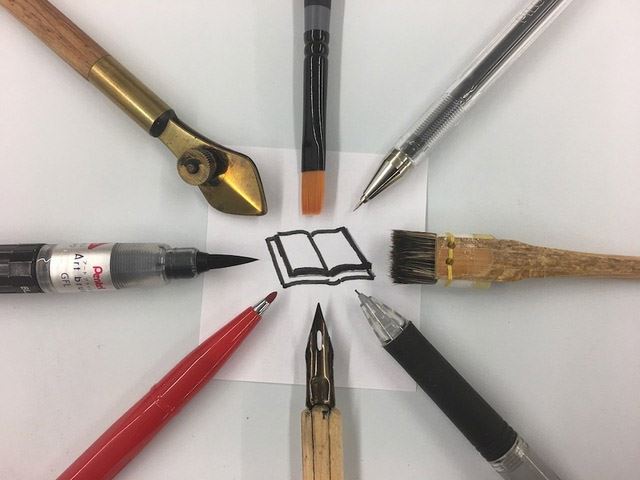

When I learned European calligraphy in the mid-1970s, I started from the beginning – wedges pressed into wet clay, using brushes and blunt reeds. Physical acts of making marks with my writing hand. I learned the seven or eight major writing styles from Trajan capitals to the Baroque copperplate of the mid-Eighteenth Century. In repeatedly tracing the “ductus” of alphabetic forms I absorbed their history and adaptations, learned context of the societies they were written in, and benefitted from their legacy. And I appreciated their formal malleability over time and culture.

Tools for opposable thumbs

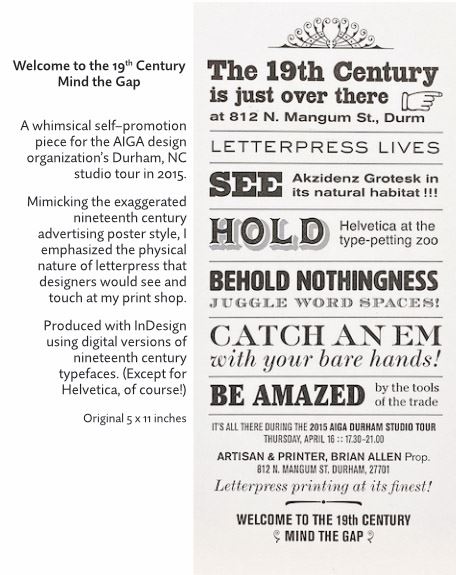

The physical actions of letterpress printing reinforce my sense of the allure of the book arts through the reconnection, and cooperation, of hand and brain. Each metal letter is a real thing to be put next to another letter. I told students in my private printing classes that in the print shop a nothing becomes a something: a word space is a real thing, with weight. Anaïs Nin writes well about the letterpress experience in Volume 3 of her Diary: 1939-1944: “You can touch the page you wrote.” “The words which first appeared in my head, out of the air, take body. Each letter has a weight. I can weigh each word again, to see if it is the right one.” Building physical structures to hold text or image equally engage hand and brain.

60 and 72 American pica point Cloister Initials, from Frederic Goudy

Frank Wilson, a neurologist, in his 1998 book “The Hand: How Its Use Shapes the Brain, Language, and Human Culture,” traces the evolution of the hand and its components and posits its influence on creating language – the hand points to or holds a thing that needs an identifying word. Our concepts about reality are largely drawn from a confirming touch. A substantial amount of the information the brain must work with comes through the sensing capacity of the hands.

Wilson also argues that American education pushes children away from manual exploration to purely intellectual activity too early, stunting the hand/brain co-development process. I believe that this, at least in part, is the source of people’s joy, exhilaration, and relief that they have found where they belong when encountering the art of the (hand) book.

Parenthetically, I think book arts programs could help other academic disciplines to reawaken the wonders of their fields by offering hands-on sessions, for example making a Jacob’s Ladder structure. Other disciplines don’t seem to pay much attention to their histories and processes like book arts does – whose skills and techniques are by nature historical. Philosophy classes would be enriched by directly experiencing the boundary of thought and touch. Wilson relates that mechanical engineering companies didn’t like to hire young engineers – they hadn’t played in a sandbox and had trouble conceptualizing the third dimension.

36 Didot point Diethelm Antiqua, released by the Haas foundry around 1950. I had acquired a run of it as part of the Swiss/Canadian shop purchase I made in 2007. I may have been the only printer in the US who had it. I speculate it was Haas’ competitor to Palatino, released a little earlier by Stempel.

Brian Allen is retired from 45 years working with letterforms, from calligraphic to phototypeset to letterpress to digital. Twenty of those years were spent in digital font production for startups, IBM, and Monotype. He enjoys the art, craft, and culture of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.